- Explain the reasons why a journalist might be represented in a manner similar to that of Jesus Christ.

- Characterize the political group that David was part of when he denounced Marat's death in the way he did.

- Point out at least two other models of representation that resemble Marat. Relate this painting to "The Entombment of Christ" and to a way of expressing the idea of compassion, struggle, and heroism for the world we live in.

In 1793 – the year David painted “The Death of Marat” – the French Revolution, which began four years earlier, was in full swing, and the country was experiencing a turbulent moment characterized by increased political violence. During this time, the Jacobin revolutionaries sought to regulate the prices of essential goods and implement laws that would make it easier for small peasants to access land. Meanwhile, outside France, the country was engaged in wars against Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain, who feared the violence and influence of the Revolution.

In January 1793, King Louis XVI lost his head to the guillotine, executed by Jacobin revolutionaries led by Maximilien de Robespierre. David and Jean-Paul Marat were colleagues of Robespierre and supported the king's decapitation. The guillotine became a popular method for eliminating political threats – real or imagined – to the Jacobin government.

Six months after the execution of the king, Marat was assassinated in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday, a sympathizer of the Girondins. With the painting “The Death of Marat,” created in the neoclassical style, David transformed his friend into a martyr. This decision is significant because, as demonstrated by his death, Marat was a central and controversial figure during the revolutionary period, working alongside some of the most radical voices of the time.

- Much of the painting is an eloquent void.

- The wounds are modest, small, inspired by representations of Christ's wounds.

- Even in death and illness, Marat appears as a figure of dignity.

- Marat's position is inspired by the painting "The Entombment of Christ" by Caravaggio, which we have already seen in this material.

- The work aims to evoke emotion and elements of theatricality. The light does not illuminate everything uniformly to emphasize this aspect.

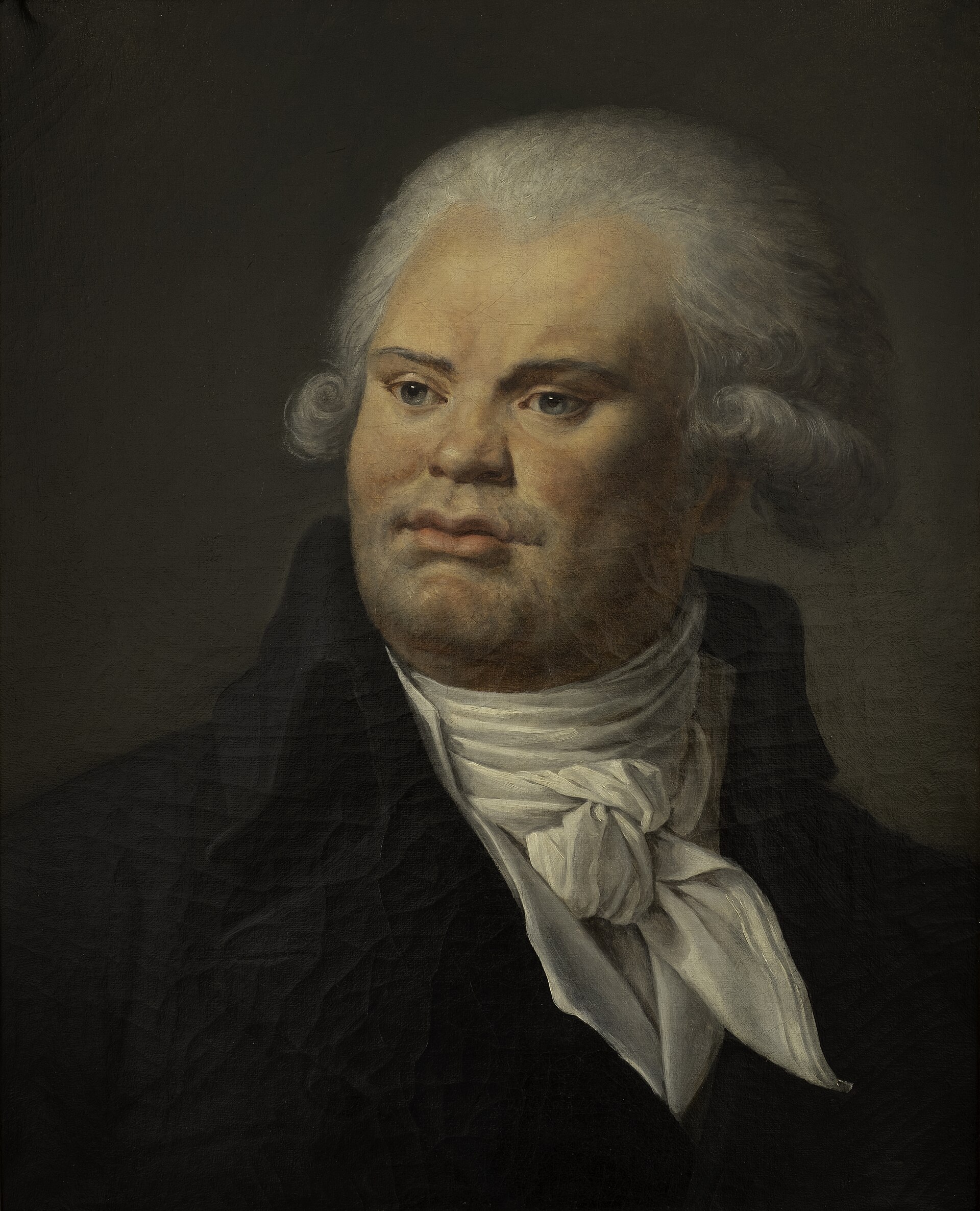

Jean-Paul Marat

Source: WikipediaJean-Paul Marat (1743-1793) was a Jacobin revolutionary and Montagnard who played a significant role in the French Revolution. He repudiated the more moderate factions of the revolution, advocating for political persecution and assassinations through his newspaper “L’Ami du peuple.” He was one of the most important revolutionary leaders, alongside Robespierre, Danton, and Saint-Just.

Robespierre

(1758-1794)

Danton

(1759-1794)

Saint-Just

(1769-1794)

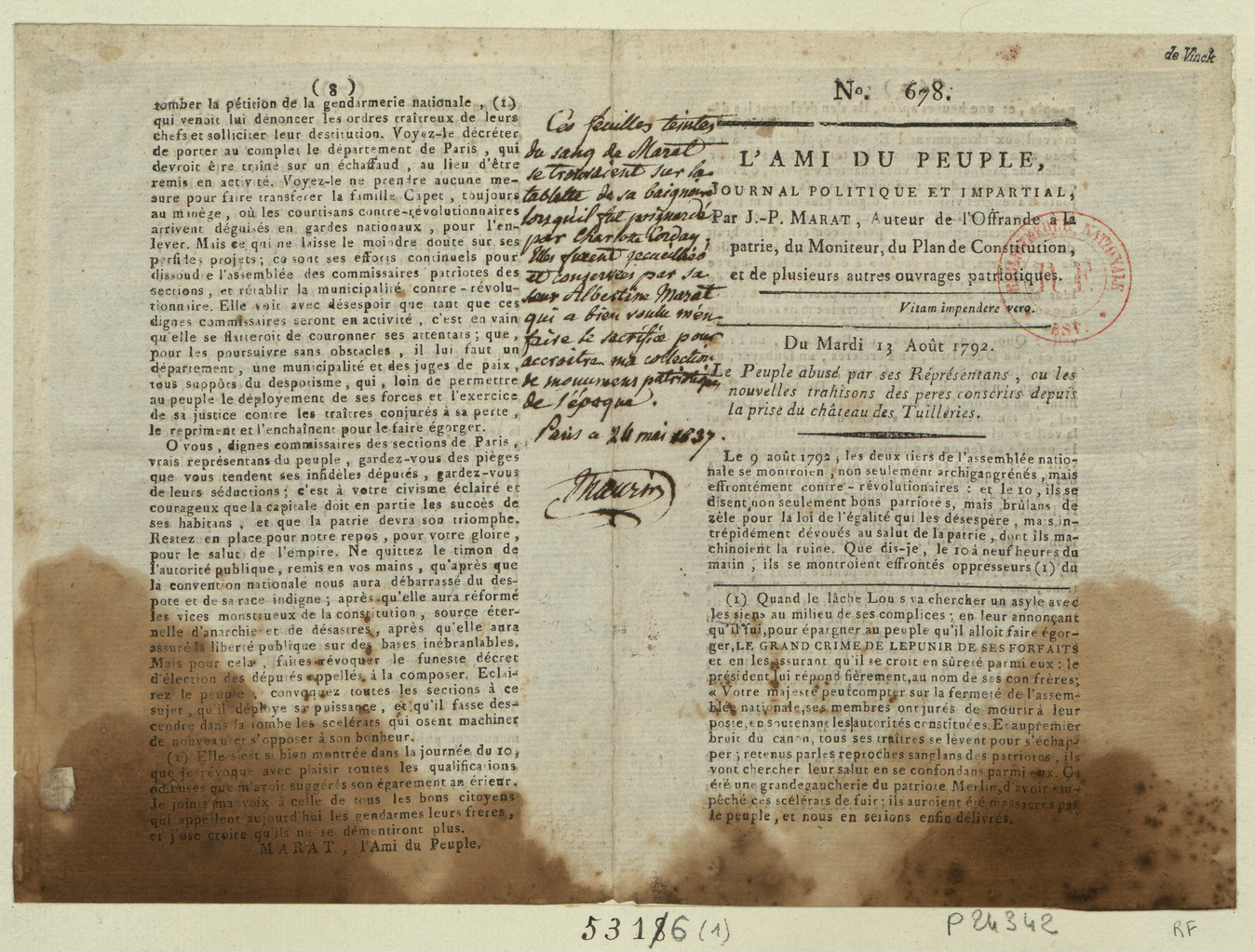

A copy of L’Ami du peuple, "The most famous radical newspaper of the Revolution," stained with Marat's blood.

Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de FranceThe newspaper, founded by Marat, was a platform for his ideas and became a powerful means of communication for the Jacobins. In it, Marat especially defended the interests of the workers and the underprivileged, using a combative and aggressive writing style.

- Jacobins: a political group that represented the third estate ("people") in the National Assembly and the National Convention. Its members were primarily from the middle and small bourgeoisie and were considered more radical than the Girondins. The Montagnards were a faction that advocated for more radical revolutionary policies within the Jacobin movement. Robespierre, Danton, Marat, Saint-Just, and David were all both Jacobins and Montagnards.

- Girondins: a political group that represented the third estate ("people") in the National Assembly and the National Convention. They were primarily from the upper bourgeoisie and were considered more moderate than the Jacobins.

- Sans-culotte: a political group associated with the Jacobins, composed of poor, urban, and radicalized workers who advocated for strong social and economic reforms.

- Plain: a political group in the center of the assembly, consisting of about 345 deputies who formed the "Plain" or the "Marais" (swamp). Determined to defend the work of the Revolution and usually voting on the left, they often acted as support for either side depending on the circumstances, leading to a sometimes-ambiguous stance regarding their positions.

Gerda Taro, Navacerrada Pass, Segovia, Spain, 1937. Published in the book Death in making.

Head of School

Fábio Marinho Aidar

Academic Director

Débora Vaz

Middle School Principal

Joana Procópio de C. F. França

Middle School Academic Coordinators

Cristiane Pires da Motta

Fernanda Luciani

8th Grade Counselor

Tiago Tavares de Lima

Instructional Designers

Maurício Ferreira Freitas (History)

Beatriz Ruffino (Library)

Paola Nogueira (Publishing)

Translator

Rodrigo A. Morato

Republic

The Renaissance embraced Greco-Roman antiquity as a true source of beauty and knowledge. However, unlike the pagans of Antiquity, the Renaissance thinkers saw themselves as living in a time after the coming of Jesus Christ, and for this reason, they believed they could achieve the aesthetic values of Classical Antiquity but produce even better works.

Renaissance Art

- Balanced and bilateral composition

- Mathematical symmetry through shapes, rhythms, and colors

- Linear perspective

- Uniform lighting that reaches the entire painting

- Well-defined lines

- Strict application of human anatomy

- Theme referencing the Greco-Roman universe

- The painting is not intended to cause an emotional impact: there is little theatricality in the composition

- Use of very balanced colors

Baroque art, associated with the Counter-Reformation movement, placed emotion before rationality. Painters primarily sought to depict Christian scenes that would create an emotional impact on the viewer.

Baroque Art

- Dramatic, emotional, and theatrical representation. The scene is depicted at the peak of the characters' emotional intensity

- The painting aims to create an emotional impact

- Strict application of human anatomy

- Non-uniform lighting with strong contrast between light and dark

- Asymmetrical composition

France in the 17th and 18th centuries was marked by political centralization around a sovereign monarch. The Palace of Versailles, built for the Sun King (Louis XVI), symbolized the luxury and excess of the aristocracy. During this same period, the rest of the population, the vast majority, found themselves alienated by the extravagance of the elites. The dominant artistic style of this era was Rococo, whose main themes were associated with frivolity and often depicted the love and daily life of aristocrats.

Rococo

- The composition is based on blended patches of paint, without well-defined lines

- Curving, sinuous elements

- Light and soft colors

- The composition is not constructed with geometry, symmetrical, or mathematical patterns

- Anatomy is less rigid, allowing for fluidity